PROJECTS

Zane Grey Estate Preservation Project

Figure 1. PaleoWest Foundation Executive Director James Potter (right) and Photographer Jason Quinlan photographing the Katchina Room at the Zane Grey Estate in Altadena

In August of 2020, the PaleoWest Foundation was contacted by Teresa Fuller of Teresa Fuller Real Estate in Pasadena, California, regarding some historical paintings in a house she was showing, which turned out to be the Zane Grey Estate in Altadena. She asked for advice on possibly preserving the paintings and in response the Foundation sponsored a professional photography shoot of the art. The paintings were done in the 1920s by Lillian Wilhelm-Smith (1872-1971), a noted watercolorist, adventurer, and illustrator for several of Zane Grey’s western novels. She was introduced to the West and its culture by Zane when she accompanied him to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. She explored and painted many of the West’s most remote areas. The images she painted in the “Kachina Room” in the Zane Grey house consist of Ye’ii (Navajo spirit deities), Puebloan Katchinas, masks, and abstracts. The light fixture in this room is made from woven Apache baskets. These images, as well as versions with scale bars, are now curated at the Museum of Northern Arizona, which houses a number of other collections related to Ms. Wilhelm-Smith.

Figure 2. Ye’ii, a Navajo spirit deity

Figure 3. Navajo Ye’ii

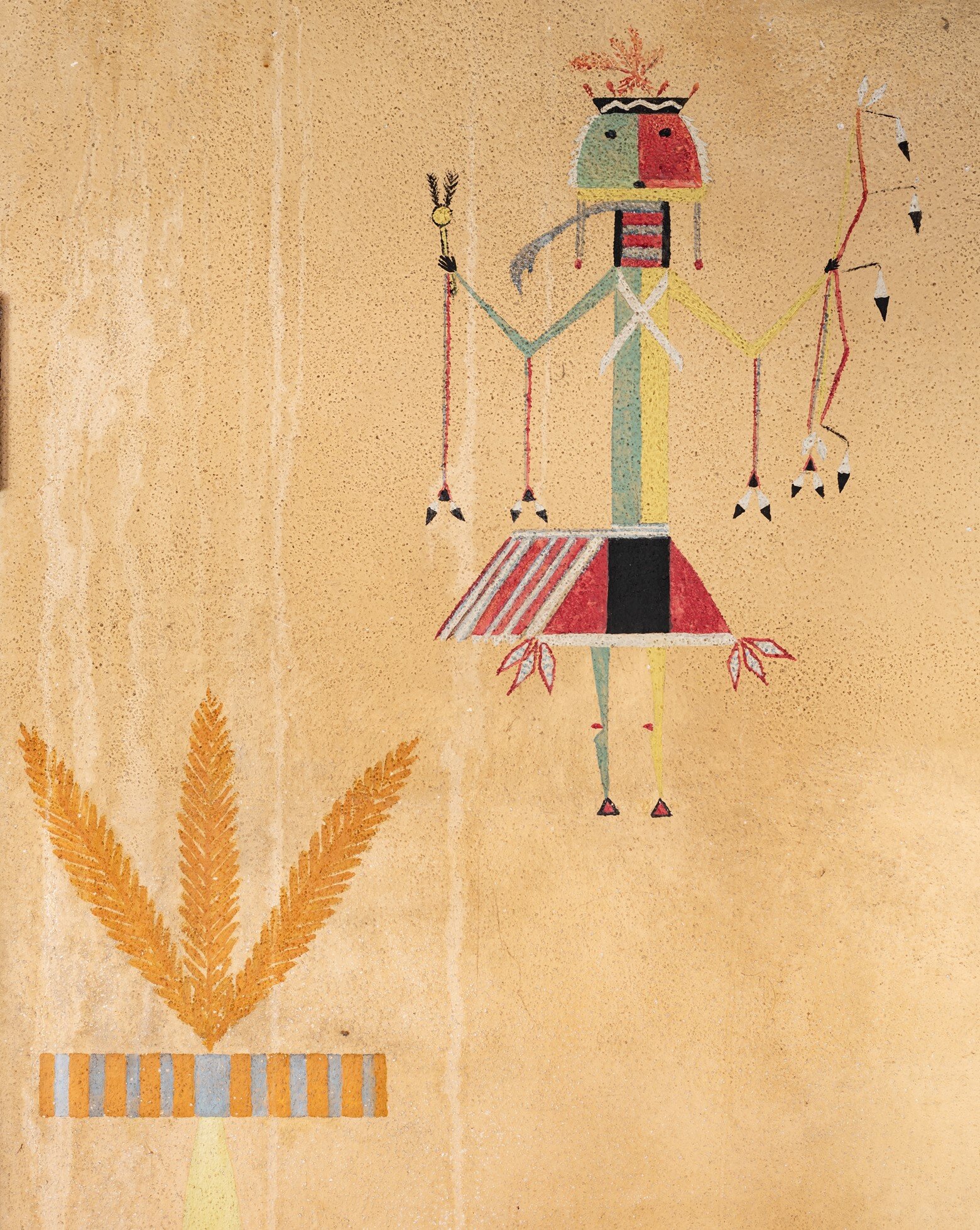

Figure 4. Niman Kachina. According to the Hopi, the spruce collar attracts rain

Figure 5. Polik-mana or Butterfly Maiden. Every spring she dances from flower to flower, pollinating the fields and flowers and bringing life-giving rain to the Arizona desert.

Figure 6. Long-beard Katchina

The Baja California Upper Gulf Project

Congratulations to Dr. René L. Vellanoweth and his international team for submitting the winning application for the 2018 PaleoWest Foundation Research Grant. The international team comprises Antonio Porcayo-Michellini (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia [INAH], Baja California), Amira F. Ainis (University of Oregon), Richard G. Guttenberg (John Minch and Associates), and William Hayden (ETI: Drones). Their multi-year project, Human Responses to Trans-Holocene Environmental Change, Baja California, Mexico aims to better understand short- and long-term human adaptations to Baja California’s Gulf coastline, coastal drainages, and offshore islands. As a binational research program, several American institutions (California State University, Los Angeles, and the University of Oregon) are collaborating with Antonio Porcayo-Michelini, an INAH (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia) archaeologist with extensive experience in the Upper Gulf region. Their research program examines the Gulf as a series of marine ecosystems influenced by daily, seasonal, decadal, and longer fluctuations as well as terrestrial influences that had direct impacts on human settlement and land use. The project assumes that these patterns are evident in the archaeological record and that predictive models about human settlement can be developed from marine ecosystem and littoral habitat reconstructions.

The Upper Gulf coast of the Baja California Peninsula contains numerous shell middens of various sizes, composed of dense faunal remains from a wide variety of shellfish taxa. In addition, lithic scatters containing a wide array of lithic tools and debris, along with lithic quarry sites are generally known from the area. Many of these sites are facing severe impact and destruction by touristic use of the sand dunes and adjacent areas for off-roading and other activities. Since 2006, Antonio Porcayo-Michelini and other INAH representatives have been working diligently to identify and officially record archaeological sites, attempting to minimize impacts to the many shell middens that stretch along this coastline. The threat of imminent destruction of these sites is obvious and only a matter of time as the area becomes more developed every year and larger numbers of tourists flock to this coastline.

In December 2017, the initial phase of this project included an intensive pedestrian survey and mapping of a ~15 km stretch of coastline south of San Felipe, which resulted in the identification of more than 30 archaeological sites and the collection of ~20 shell and charcoal samples for radiocarbon dating. Many of these sites sit on eroding dunes and have been disturbed to varying degrees, however, several intact components were noted and selected for further investigation (Figure 1), including one site where hundreds of fish otoliths were collected from the surface within minutes (Figure 2). The gathering of these data will allow the construction of a cultural chronology for human occupation of this section of coastline along the western coast of the Upper Gulf of California, Mexico.

Figure 1. One of the newly recorded coastal shell midden sites revealing intact components for archaeological testing.

Figure 2. One of the several bags of fish otoliths collected from the surface of one of the newly identified coastal shell midden sites. Most of these otoliths belong to the Totoaba, an endemic fish that is now critically endangered.

GPS/GNSS locational data of identified sites was collected and mapped in GIS and aerial POV photography was captured by a 3DR Solo Quadcopter drone (Figure 3; courtesy of ETI: Drones), providing excellent geographic imagery for further analysis. In addition to the newly identified coastal shell midden sites, this combination of GIS and drone technology were used to map and visually record several archaeological sites, including a lithic quarry site of rhyolitic material (Figure 4) and an historic mining site (Figure 5).

Figure 3. 3DR Solo Quadcopter drone technology used for aerial survey. Generously provided by ETI: Drones.

The 2018 PaleoWest Foundation grant will fund future phases that will include continuing coastal surveys, test excavations at several sites, more intensive collection of datable samples and detailed faunal and artifact analyses. The compilation of a large suite of radiocarbon dates for archaeological deposits in the project area will allow them to construct a cultural chronology and shed light on the nature of human habitation, subsistence, and resource use in this area through time.

Figure 4. Detailed GIS mapping at a lithic quarry site.

The geographic area encompassing the Colorado River Delta and Upper Gulf of California was an important cultural intersection in the past, where several cultural groups from the southwestern United States and the Baja Peninsula interacted in trade networks that extended throughout much of western North America (i.e., Massey 1949; Laylander 2005; Rogers 1945). Environmentally, this area has attracted the attention of modern biologists and conservationists interested in the marine ecosystems of the Colorado Delta and Upper Gulf, which have undergone enormous alterations in the past 100 years. The propensity for rapid shifts in the relatively fragile ecosystems that develop in delta, estuary, and shallow coastal platforms make this an ideal location to investigate oscillations in littoral ecosystems throughout the climatically variable Holocene epoch and the subsequent adaptations adopted by hunter-gatherer-fishers of the Upper Gulf.

This project creates relevant knowledge that is sorely needed in current management and conservation efforts intent on preserving and protecting negatively impacted cultural resources and depleted Gulf fisheries, which have suffered under decades of unsustainable commercial fishing, increased pollution, and severe habitat modifications (i.e., damming of rivers and tributaries, etc.). Marine biologists, however, are constrained by the short temporal limits of their data sets, which only extend a few decades at best. Archaeological data, like that collected in this project, are unique and can extend historical ecologies of specific habitats, coastlines, and deltas thousands of years into the past. As such, it directly contributes to the protection and preservation of cultural and natural resources of the area today and is a benefit to local communities.

Figure 5. Overview of the Historic Era mining camp that was recorded and mapped using drone technology (Courtesy of ETI: Drones).

The Langtang Recovery Project

In April of 2017, the PaleoWest Foundation sent Shawn Fehrenbach to Nepal in order to assess the potential for developing a collaborative project between the Foundation and the non-profit relief organization Flagstaff International Relief Efforts (FIRE).

FIRE has been working on relief projects in the Langtang Valley, north of Kathmandu since the valley and the village of Langtang were devastated by landslides and structural collapses following a series of strong earthquakes in the region in 2015. (View their webpage on Langtang here: http://www.fireprojects.org/nepal/langtang/). While there was an initial outpouring of immediate international relief funds and programs into the region and into Nepal, there has been comparatively little focus on sustained recovery projects. This is the focus of FIRE.

In addition to Shawn, the trip included a filmmaker interested in collaborative ethnographic documentation, a nurse interested in local medicinal practices and developing local medical treatment capacity in the valley, and an engineer interested in local construction techniques with an eye on earthquake resistant construction practices.

The Langtang Valley is a deep valley in the Himalayan mountains that provides one of Nepal’s lesser-traveled, but still active trekking routes. Before the 2015 quakes, Langtang village was the largest in the valley. The older portions of the village sat just up the valley to the east of a large hanging glacier on the north wall of the valley. When the earthquakes struck late in the morning of April 25, 2015, the glacier let loose, completely annihilating the western part of Langtang village with the force of a small nuclear blast. According to locals, about 300 died, with approximately half of those being locals from the Langtang Valley, and the rest split roughly evenly between foreign trekkers and Nepalis from elsewhere in the country. Approximately 90 of the 300 are said to still not have been identified.

A large amount of snow and ice came down with the glacier. The area of the landslide is massive, perhaps half a kilometer wide and stretching from the valley wall to the bottom of the valley. It now looks like a moonscape of rubble, which appears to be glacial rubble deposited as the landslide has melted down over the past two years. Just to the west of the landslide area, there was a small village called Gomba after the most significant buddhist monastery (gomba means monastery) that was located here with a dozen or so surrounding buildings. This area and its structures were wiped out by falling snow and ice, but not the glacier. It has just now, after two years, melted completely out of this snow and ice fall, and is not buried by glacial rubble as with just further up the valley. Today, it appears similar to many archaeological ruins, a concentration of foundations and partial stone masonry wall features with artifacts strewn about.

As a result of this reconnaissance visit to Langtang, Shawn has identified several prospects for recovery work that meet the mission statement goals of the Foundation. The primary one would be an excavation project in Gompa coupled with a 3D modeling program in the area and surrounding landscape, including the glacial landslide itself. Excavations in Gompa might have two main objectives: to recover any information on architecture that could be useful in efforts to rebuild using traditional methods and to recover for the community any relics or other valuable artifacts not yet recovered from the ruined monastery. 3D modeling would focus both on the ruins in Gompa to assist these excavations, but would also be useful in a drone mapping program of the valley landscape, particularly the glacial landslide area to provide volumetrics and other data that could be shared among scientists and relief organizations working in the area to assist relief, recovery, and investigative efforts.

We at the Foundation hope to continue our support of the project and will keep you posted on its status and the results of any future fieldwork.

Evidence of the landslides remain scattered throughout the valley.

Residents press on with the task of rebuilding their community.

The Cedar Mesa Perishables Project: Restoring the Research Potential of a Forgotten Archaeological Collection

Congratulations to Dr. Laurie Webster, the winner of the 2017 PaleoWest Foundation Research Grant for 2017. Dr. Webster’s project is part of a multi-year effort to document and interpret the approximately 4,000 Basketmaker and Pueblo-period perishable artifacts excavated from alcove sites in southeastern Utah during the 1890s. These extraordinary collections are housed in six major museums outside of the Southwest. The aspect of the project funded by the PaleoWest Foundation will be to complete the documentation of the vast collection at the American Museum of Natural History.

Dr. Webster’s proposal requested funding to travel to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York to survey and photo-document approximately 650 archaeological textiles, baskets, wooden implements, hides, and other perishable artifacts recovered from dry caves in southeastern Utah. Dating to the Basketmaker (ca. 500 B.C.-700 A.D.) and Ancestral Pueblo (700-1300 A.D.) periods, the artifacts were collected between 1892 and 1897 by amateur archaeologists Richard Wetherill, Charles McLoyd, and Charles Cary Graham. Now part of the Hyde, Whitmore, and Kunz collections at the AMNH, nearly all of these objects are still unpublished and unknown to archaeologists, the general public, and descendent native communities.

The goals of the larger project are (1) to survey, photo-document, and interpret the archaeological textiles, baskets, wooden implements, hides, and other organic artifacts in these collections, and (2) to make them more widely known to archaeologists, the general public, and native communities through public presentations, publications, and the establishment of two project archives. Since the project’s inception, it has documented more than 2,700 perishable artifacts, generated more than 8,000 digital images, and processed 16 radiocarbon dates.

Cowboy Wash Pueblo

Preservation Project

In 2016, the PaleoWest Foundation provided support for CU Boulder’s archaeological field school. Led by Scott Ortman of CU Boulder and Jim Potter of PaleoWest Archaeology, 12 undergraduate and 3 graduate students investigated and excavated Cowboy Wash Pueblo, a late 13th century village on the southern piedmont of Sleeping Ute Mountain in Colorado near the Four-corners. The site is the largest and latest settlement within the larger Cowboy Wash community. It is on Ute Tribal lands and the project has the full support of the Ute THPO and Tribal Council.

The project focused on recovering data from features that were in peril of eroding into the wash. Units were excavated into the fill of an exposed kiva and in an associated surface room. The fill sequence of the kiva proved to be informative, indicating that this structure was left to deteriorate naturally—the floor was capped by wind- and water-lain sediment and the structure was neither burned nor salvaged (four unburned tree-ring samples were recovered from the 1 x 2 m unit). This suggests a very late occupation for this feature, and by extension the site, which appears to represent the very final occupation prior to regional depopulation. The data from these excavations then, coupled with previous research at earlier sites in the community, have the potential to inform us about the conditions that led to the abandonment of the region and how occupants of this marginal environment coped with climate change over seven centuries (AD 600-1285).

Additionally, the PaleoWest Foundation has awarded a research grant to support analysis and write-up of the results of the excavations at Cowboy Wash Pueblo. Pottery analysis is currently being conducted by Dr. Donna Glowacki and her students at University of Notre Dame. Dr. Fumi Arakawa of New Mexico State University will analyze the chipped stone assemblage. And the final report will be written and produced by Dr. Jim Potter of PaleoWest Archaeology. Faunal, tree-ring, flotation, and botanical analyses will also be conducted and included in the results.

Several students are participating in the analysis and interpretation of the data. Dr. Glowacki and her students will present a poster at the SAAs in 2017 on the results of the pottery analysis. As well, one of Dr. Ortman’s students is writing her senior thesis on the fill sequence of the kiva and the chronology of the site.

Students excavate exposed deposits at Cowboy Wash Pueblo.

Post-excavation photo of kiva fill. Note plastered floor and tree-ring samples in profile.

Paleodiet of Turkeys at

Six Early Ancestral Puebloan Habitations

In 2016, the PaleoWest Foundation awarded a grant to Harlan McCaffery of Statistical Research, Inc. and Kye Miller, PaleoWest Archaeology to investigate the paleodiet of turkeys in early villages in northern New Mexico. The research project will involve stable isotope and radiocarbon analyses of turkey skeletal remains from six Basketmaker III – Pueblo I contexts in northern New Mexico to assess domestication through dietary practices. The analysis has the potential to determine the degree of maize consumption by domesticated turkeys during the pithouse to pueblo transition and will allow us to compare the degree of maize consumption by turkeys kept by contemporary, but differing, social groups.

The Basketmaker III – Pueblo I period in northern New Mexico is characterized by the development of pottery, pit house villages, and increasing reliance on domesticates. The purpose of the research is to examine the paleodiet of turkeys during this formative period; specifically, to determine whether turkeys ate maize, and to estimate the amount of maize in their diets. The research will build on previous paleodietary studies of turkeys from Basketmaker III through Pueblo III (AD 500–1300) contexts in and around the San Juan Basin (Lipe et al. 2016; McCaffery et al. 2014; Rawlings and Driver 2010). By testing turkey bones from earlier sites, we can answer questions about the timing and the nature of turkey domestication in northern New Mexico: how reliant were domesticated turkeys on human crops during the eighth and ninth centuries A.D.? Were the first villages in the region settled prior to the incorporation of domestic turkeys into the human food system, or did they develop at the same time? Were turkeys deposited in ritual contexts (such as a turkey burial at NM-Q-18-302) the first domesticated birds, while ones used for food were still being hunted in the Basketmaker and early Pueblo periods? What were the differences in level of domestication among distinct cultural groups?

The chosen method for this research is stable isotope analysis. This is a minimally destructive analysis and will involve taking a sample of each just 1 gram from a small bone fragment. For this study we would look to test 19 bones. The method measures stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen in bone collagen components of the bone using a stable isotope mass spectrometer. The relative contribution of C4 plants, such as maize, and C3 plants to the diet can be inferred from these measurements. This method is well-researched and has been used in numerous paleodietary analyses of human and faunal remains following a landmark study by Vogel and van der Merwe (1977,1978). The analysis would be conducted at the University of South Florida (USF) Laboratory for Archaeological Science under the direction of Prof. Robert Tykot. Tykot’s abundant experience extends over two decades, including previously serving as the Laboratory Manager of Archaeometry Laboratories at Harvard University. McCaffery et al. (2014) successfully used the same lab for the previous study of Pueblo II-III turkey bones recovered along the Middle San Juan River in northwest New Mexico.

PaleoWest Foundation funds are being used to conduct the stable isotope analysis at USF. Depending on the results of the stable isotope analysis, the researchers intend to apply for a second round of funding to cover the costs of AMS dating of particular samples. They ultimately intend to publish the research in a peer-reviewed regional journal, curate the research in an accessible digital format (i.e., tDar), and present the research at national and regional conferences.